Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals

58 Canal Circular Road,

Kolkata - 700054, WB, India.

Contact : +91 9874167730 / +91 9830363642

Email : pchakrabarti@usa.net

Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals

58 Canal Circular Road,

Kolkata - 700054, WB, India.

Contact : +91 9874167730 / +91 9830363642

Email : pchakrabarti@usa.net

Dialysis is a treatment for severe kidney failure (also called renal failure, stage 5 chronic kidney disease, and end-stage renal disease). When the kidneys are no longer working effectively, waste products and fluid build up in the blood. Dialysis take over a portion of the function of the failing kidneys to remove the fluid and waste

Dialysis is typically needed when about 90 percent or more of kidney function is lost. This usually takes many months or years after kidney disease is first discovered. Early in the course of kidney disease, other treatments are used to help preserve kidney function and delay the need for replacement therapy.

Once dialysis becomes necessary, you (along with your physicians) should consider the advantages and disadvantages of the two types of dialysis:

Haemodialysis (in-centre or at home)

Peritoneal dialysis

The choice between haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis is influenced by a number of issues such as availability, convenience, underlying medical problems, home situation, and age. This choice is best made by discussing the risks and benefits of each type of dialysis with a healthcare provider.

You and your doctor will make the decision about when to start dialysis as your kidney disease progresses. Your kidney function (as measured by blood and urine tests), overall health, nutritional status, symptoms, quality of life, personal preferences, and other factors impact the decision. Healthcare providers recommend that dialysis begin well before kidney disease has advanced to the point where life threatening complications can occur.

It is generally possible to be put on a kidney transplant waiting list when kidney function is about 20 percent of normal. Many patients will need to start dialysis when their kidney function is about 8 to 12 percent of normal, although this is variable.

In certain situation, dialysis must be started immediately. If blood tests indicate the kidneys are working very poorly or not at all, or if there are symptoms such as confusion or bleeding that is related to kidney disease, dialysis should be started at once.

Preparations for haemodialysis should be made at least several months before it will be needed. In particular, you will need to have a procedure to create an "access" (described below) several weeks to months before haemodialysis begins.

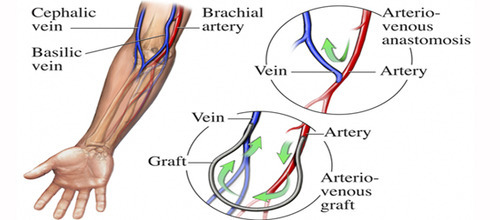

Vascular access: An access creates a way for blood to be removed from the body, circulate through the dialysis machine, and then return to the body at a rate that is higher than can be achieved through a normal vein. There are three major types of access: primary AV fistula, synthetic AV bridge graft, and central venous catheter. Other names for an access include a fistula or shunt.

The access should be created before haemodialysis begins because it needs time to heal before it can be used. Discussions about the access should begin even earlier, since you will need to avoid injuring blood vessels that will eventually be used for access. Having an intravenous line (IV) or frequent blood draws in the arm that will be used for access can damage the veins, which could prevent them from being used for a haemodialysis access. The access is usually created in the non-dominant arm; for a right-handed person this would be their left arm.

After the access is placed, it is important to monitor and care for it over time.

Primary AV fistula: A primary AV fistula is the preferred type of vascular access. It requires a surgical procedure that creates a direct connection between an artery and a vein . This is often done in the lower arm, but can be done in the upper arm as well. Sometimes a vein that would not normally be useful for creating an AV fistula can be moved so that it is more accessible; this is often done in the upper arm.

This figure depicts a primary AV fistula, which creates a direct connection between an artery and a vein. This is often done in the lower arm, but can be done in the upper arm as well.

Grafts heal more quickly than fistulas and can often be used about two weeks after they are created. However, complications such as narrowing of the blood vessels and infection are more common with grafts than with AV fistulas.

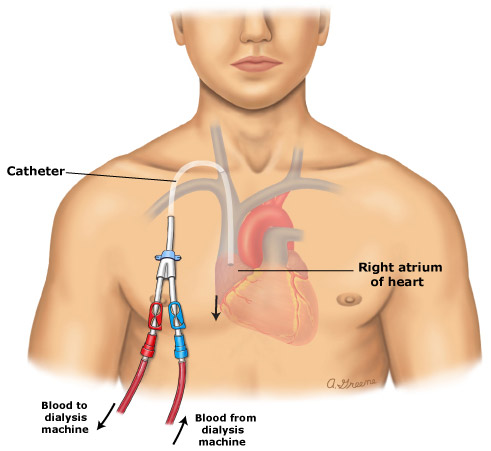

Central venous catheter - A central venous catheter uses a thin flexible tube that is placed into a large vein (usually in the neck) (figure 3). It may be recommended if dialysis must be started immediately and the patient does not have a functioning AV fistula or graft. This type of access is usually used only on a temporary basis. In some cases, however, there can be problems maintaining an AV fistula or graft, and the central venous route is used for long-term access.

This figure depicts a central venous catheter, which uses a thin flexible tube that is placed into a large vein (usually in the neck).

Catheters have the highest risk of infection and the poorest function compared to other access types; they should be used only if a primary fistula or synthetic bridge graft cannot be maintained.

Some patients, especially those who receive dialysis in a centre, will need to make changes in their diet before and during haemodialysis treatment. These changes ensure that you do not become overloaded with fluid and that you consume the right balance of protein, calories, vitamins, and minerals.

A diet that is low in sodium, potassium, and phosphorus may be recommended, and the amount of fluids (in drinks and foods) may be limited. A dietician can help you to choose foods that are compatible with haemodialysis treatment.

Haemodialysis can be done at a dialysis centre or at home.

Home treatment requires that you and your family have training and ongoing support from healthcare providers who are experienced in treating patients with home haemodialysis. This usually includes a nephrologists (kidney specialist) and specially trained nurses. Patients treated with home haemodialysis can often lead more independent lives and may have improved survival outcomes compared to those treated in a dialysis centre. This is due, in part, to home haemodialysis patients having more frequent or longer dialysis treatments than those treated in a dialysis centre. Home dialysis is generally done three to seven times per week and takes between three and ten hours per session. Haemodialysis that is done during the daytime is often done for about three to four hours, four to seven days each week. Haemodialysis that is done at night (called nocturnal haemodialysis) is typically done three to seven times weekly while you are sleeping. Additional time is needed to prepare and clean up. Home dialysis can be done at a time that is convenient for you. You are generally required to have someone else (a family member, friend, or technician) to assist you before, during, and after dialysis. A healthcare provider must be available by telephone in case questions or problems arise; some machines allow you to be monitored remotely via the telephone or internet. A daily (or nightly) dialysis schedule provides substantial benefits compared to in-centre, three times weekly haemodialysis. More frequent dialysis results in a significant improvement in your well being, reduces symptoms during and between dialyses, and improves quality of life. Home haemodialysis can improve your quality of life because it allows you to assume more responsibility for your own care and allows you to remain in the comfort of your home during treatment. In addition, patients who use home haemodialysis are often able to continue working.

Home haemodialysis requires that you have a dialysis machine in your home. Depending upon the machine, additional supplies may be needed, including water treatment tanks, dialysers, bottles of dialysate, bleach and disinfectant, syringes, needles, medications, blood tubes, and water test kits. Some machines require electrical and plumbing modifications in the area of the home where dialysis will be done. Currently available home haemodialysis machines are approximately the size of a bedside table. Newer home haemodialysis systems are portable and can be used while travelling, although many patients who use home haemodialysis and wish to travel make arrangements for in-centre dialysis at the location where they will be travelling.

Dialysis may be done in a hospital, a clinic associated with a hospital, or a free-standing clinic. Centres are staffed with physicians, nurses, and patient care technicians, all of whom participate in your care. In general, in-centre haemodialysis takes between three and five hours (the average is three and a half to four hours) and is done three times a week. You will be able to read or sleep during treatment, and you usually have access to a television. Eating, drinking, and visitors are usually restricted in a dialysis centre.

Dialysis centres are located throughout the United States and in many locations around the world. Patients who require dialysis but wish to travel can make an appointment at a dialysis centre in the location where they will be travelling (called a transient centre). Many dialysis centres have a staff member, either a nurse or social worker, who can help arrange the appointment; planning should begin six to eight weeks in advance to ensure that space is available. The dialysis centre where you normally have dialysis treatments will need to provide information to the transient centre about your medical history, including recent test results and treatment records, a list of medications, insurance information, and any special requirements. Patients with chronic medical problems, including those who require dialysis, should plan carefully for travel away from home. This may include carrying extra medications and written prescriptions, a medical identification device, and a list of healthcare provider contact information.

Patients who use haemodialysis, either at home and in-centre, will be monitored with blood tests to ensure that the time and type of dialysis treatments (called dialysis prescription) are optimal. Studies have shown that the correct dialysis prescription improves health, prevents complications, and prolongs survival. Blood testing is done at least once per month, and adjustments to the dialysis prescription may be made based upon the results of testing.

Because kidneys that are failing cannot remove enough fluid from the body, dialysis must perform this task. Accumulation of fluid between haemodialysis treatments can lead to complications. Most patients will be weighed before and after dialysis, and will be asked to monitor their weight on a daily basis at home. If your weight increases more than usual between treatments, contact your healthcare provider.

It is important to take care of your access to prevent complications. Complications can occur even if you are careful, but are much less common if you take a few precautions:

Wash the access with soap and warm water each day, and always before dialysis. Do not scratch the area or try to remove scabs. Check the area daily for signs of infection, including warmth and redness. Check that there is blood flow in the access daily. There should be a vibration (called a thrill) over the access. If this is absent or changes, notify your healthcare provider. Sometimes, flow monitoring is done during the dialysis treatment using ultrasound (sound waves). The flow monitoring measures the speed of blood flow during dialysis treatment. Take care to avoid traumatizing the arm where the access is located; do not wear tight clothes, jewellery, carry heavy items, or sleep on the arm. Do not allow anyone to take blood or measure blood pressure on this arm. Rotate needle sites on the access. Use gentle pressure to stop bleeding when the needle is removed. If bleeding occurs later, apply gentle pressure; call a healthcare provider if bleeding does not stop within 30 minutes or if bleeding is excessive.

Most patients tolerate haemodialysis well. However, side effects of haemodialysis can occur. Low blood pressure is the most common complication and can be accompanied by light-headedness, shortness of breath, abdominal cramps, muscle cramps, nausea, or vomiting. Treatments and preventive measures are available for the discomforts that can occur during dialysis. Many of these side effects are related to excess salt and fluid accumulation between dialysis treatments, which can be minimized by carefully monitoring how much salt and fluid you consume.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a procedure that can be used by people whose kidneys are no longer working effectively. The procedure is performed at home and works to remove excess fluid and waste products from the blood. This topic discusses peritoneal dialysis. Other treatments for chronic kidney disease are discussed separately.

As the kidneys lose their ability to function, fluid, minerals, and waste products that are normally eliminated in the urine begin to build up in the blood. When these problems reach a critical stage, excess fluid and waste must be removed with renal replacement therapy. There are two types of dialysis: haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Kidney transplantation may be an option for some patients, although dialysis is the most commonly used treatment. The "best" type of dialysis depends upon your abilities, underlying medical illnesses and personal needs. These issues are discussed separately. It usually takes many months or years after kidney disease is first discovered before dialysis is necessary. However, some patients have a rapid decline in kidney function and occasionally severe kidney failure is discovered for the first time in people who were not previously known to have kidney disease. You and your doctor will decide together when to begin dialysis after considering a number of factors, including your kidney function (as measured by blood and urine tests), overall health, and personal preferences.

Advance planning - People with kidney disease should discuss the possible need for dialysis early in their treatment course. Advance planning allows the physician to choose a therapy that will best meet the patient's lifestyle and needs. In addition, advance planning allows the physician time to plan for the placement of a peritoneal dialysis catheter in the abdomen. After the catheter is placed, the patient and family will be trained by the staff at the home dialysis unit on how to set up the equipment and become familiar with the procedures used in peritoneal dialysis. During most of this "training", the patient will actually be doing dialysis.

Before peritoneal dialysis can begin, a catheter (thin tube) must be inserted in the abdomen to carry fluid into and out of the abdominal cavity. The catheter is made of a soft, flexible material (usually silicone) and has cuffs (like balloons) that inflate to hold the catheter in place. The end of the catheter inside the abdomen has multiple holes to allow fluid to flow in and out. The catheter is placed on the left or right of the umbilicus (belly button); the patient may be given general or local anaesthesia before the insertion procedure. Although the catheter can be used right away, it is best to wait 10 to 14 days after placement before dialysis is performed; this allows the catheter site to heal. In some cases, a small volume of fluid can be exchanged during this time. Your healthcare provider will provide more detailed instructions.

Care of the catheter and the skin around the catheter (called the catheter site) is important to keep the catheter functioning and also to minimize the risk of developing an infection.

After the catheter is inserted, the insertion site is usually covered with a gauze dressing and tape to prevent the catheter from moving and keep the area clean. The dressing is usually changed at the dialysis home training centre seven to 10 days after placement. If a dressing change is needed before this time, it should be done by a specially trained peritoneal dialysis nurse using sterile techniques. The catheter should not be moved or handled excessively because this can increase the risk of infection. The area should be kept dry until it is well healed, usually for 10 to 14 days. This means that you should not take a shower or bath or go swimming during this time. A washcloth or sponge may be used to clean the body, although you should be careful to keep the catheter and dressing dry. While healing (two to three weeks), you will be asked to limit lifting and vigorous exercise.

Avoid constipation - It is important to avoid becoming constipated after the catheter is inserted. Straining to move the bowels can increase the risk of developing a hernia (a weakness in the abdominal muscle). In addition, not moving the bowels regularly can lead to problems with catheter function (slow drain time or difficulty draining the abdomen completely).To avoid constipation, your healthcare provider may recommend a diet that is high in fibre, as well as a stool softener or laxative.

After the catheter site has healed (approximately two weeks after insertion), your dialysis nurse will instruct you on catheter exit site care. It will be important to keep the area clean to minimize the risk of skin infection as well as infection inside the abdomen (called peritonitis). The skin around the catheter site should be washed daily or every other day with antibacterial soap or an antiseptic (either povidone iodine or chlorhexidine). The soap should be stored in the original bottle (not poured into another container). Other types of cleansers, such as hydrogen peroxide or alcohol, should NOT be used unless directed by a healthcare provider.

Before cleaning the area, wash your hands with soap and water and put on clean gloves. Hold the catheter still during cleaning, which helps prevent injury to the skin. Do not pick at or remove crusts or scabs at the site. Pat the skin around the site dry after cleaning. A clean cloth or towel is suggested. Apply a prescription antibiotic cream to the skin around the catheter with a cotton-tip swab every time the dressing is changed. Avoid using tapes or dressings that prevent air from reaching the skin. The site should be covered with a sterile gauze dressing, which should be changed every time the site is cleaned. The catheter should be anchored to the skin with tape or a specially designed adhesive.

With appropriate catheter placement and exit site care, most PD catheters are problem free and work for many years. If the catheter no longer works or is needed, a minor surgical procedure is required to remove it.

After the first two weeks, the skin around the catheter should not be red or painful. The skin should feel soft. There may be a small amount of thick yellow mucus discharge around the catheter. A crust or scab may form every few days. If the skin is reddened, painful, firm, or there is pus-like discharge around the catheter, there may be an infection.

If there is an injury to the catheter site, such as an accidental pull on the catheter, or if the catheter is moved excessively, a short course of oral antibiotics may be recommended to prevent infection from developing inside the abdomen (peritonitis). Most dialysis units recommend that you call if you injure the catheter site to determine if further evaluation or treatment is needed.

In peritoneal dialysis, dialysis fluid (called dialysate) is infused into the abdominal cavity (called the peritoneal cavity) through a catheter. The fluid is held (dwells) within the abdomen for a prescribed period of time; this is called a dwell. The lining of the abdomen (the peritoneum) acts as a membrane to allow excess fluids and waste products to pass from the bloodstream into the dialysate. When the abdomen is full of dialysate, you may have a feeling of fullness or bloating, although you should not feel pain. Most patients have no abnormal sensations. When the dwell is completed, the "used" dialysate can then be drained out of the abdomen (called an exchange) into a sterile container or into a shower or bathtub. This used fluid contains the excess fluid and waste from the blood, which is usually eliminated in the urine. The peritoneal cavity is then filled again with fresh dialysate. The process may be done manually four to five times during the day by infusing the fluid into the abdomen and later allowing it to run out by gravity. The process of emptying and filling for each exchange takes 30 to 40 minutes when done manually. The exchange may also be done using a machine (called a cycler).

Several different types of peritoneal dialysis schedules are possible. The "right" type of peritoneal dialysis depends upon an individual's situation. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) involves multiple exchanges during the day (usually three) with an overnight dwell. A machine is not needed and the person can walk around while the fluid is in the abdomen. At bedtime, dialysate is infused and is drained upon awakening. Occasionally, a machine (called a minicycler) will be needed to perform an exchange one or more times while sleeping. Continuous cycler peritoneal dialysis (CCPD) is an automated form of therapy in which a machine performs exchanges while the patient sleeps; there may be a long daytime dwell, and occasionally a manual daytime exchange. In developed countries such as the United States, CCPD is performed more commonly than CAPD.

Patients are often allowed to choose between CAPD and CCPD based upon lifestyle or personal issues. CCPD allows significantly more uninterrupted time for work, family, and social activities than CAPD. There may be changes in treatment type, dwell time, number of exchanges, or type of dialysate after beginning treatment, based upon how the body responds. Periodic blood and urine tests, as well as tests of the used dialysate, are used to fine tune PD treatment.

One of the most serious complications of peritoneal dialysis is infection, which can develop in the skin around the catheter or inside the abdominal cavity (called peritonitis). Another potential but less serious complication of peritoneal dialysis is the development of a hernia, a weakness in the abdominal muscle.

The signs of catheter site infection include: Redness, firmness, or tenderness of the skin around the catheter Pus-like drainage from the area

Peritonitis is the term used to describe an infection of the abdominal cavity. People who use peritoneal dialysis are at increased risk of peritonitis because bacteria can enter the abdomen through or around the peritoneal dialysis catheter. These infections can usually be treated at home and resolve completely.

Left untreated, peritonitis can become a life-threatening infection. Signs of peritonitis may include one or more of the following:

Abdominal pain, which may be mild to severe

Cloudy used dialysate fluid

Fever (temperature greater than 100.4ºF or 38ºC)

Nausea or diarrhoea

If there are any signs of infection, you need to be seen by a healthcare provider and begin treatment as soon as possible. The type of treatment used depends upon the severity and location of the infection. Peritoneal dialysis is usually continued as the infection is being treated.

Catheter site infections are often treated with an antibiotic cream and/or oral antibiotics, as well as more frequent skin cleaning. Most mild infections resolve with treatment within one to two weeks. If the infection does not resolve, the catheter may need to be removed and replaced.

Peritonitis usually requires treatment with antibiotics, which are commonly given with the dialysate (eg, intraperitoneal dosing). A change in the dwell time and/or dialysis prescription is sometimes needed temporarily. Less commonly, the peritoneal dialysis catheter must be removed and the person will be transitioned to hemodialysis.

Hernia is the medical term for a weakness in the abdominal muscle. People who use peritoneal dialysis are at risk of developing a hernia for several reasons, including the increased stress on the muscles of the abdomen (as a result of the weight of the dialysate) and the opening in the abdominal muscle created by the peritoneal dialysis catheter. Hernias can develop near the belly button (umbilical hernia), in the groin (inguinal hernia), or near the catheter site (incisional hernia).

Signs of a hernia include painless swelling or new lump in the groin or abdomen. If you develop signs of a hernia, contact your healthcare provider but continue to perform peritoneal dialysis regularly. Treatment of a hernia generally involves surgery.

Chronic kidney disease is a lifelong condition that requires lifelong treatment. Peritoneal dialysis is one option for lifelong treatment, with other options including haemodialysis and kidney transplantation. It is sometimes necessary to switch from one form of treatment to another as circumstances change.

Diet - People who undergo dialysis, both haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, are often required to make changes to their diet. In general, people who use peritoneal dialysis have a less restricted diet compared to those who use in-centre haemodialysis. Dietary changes help to ensure that the body has an adequate, but not excessive, amount of protein and certain minerals.

People who use peritoneal dialysis lose protein with every exchange, which usually means that they must eat an increased amount of protein in the diet. Protein is found in meat, milk, chicken, fish, and eggs; lower quality protein is found in some vegetables and grains. A dietician can provide specific recommendations about how much and what type of protein is needed.

Other changes in diet may include reducing the amount of foods eaten that contain phosphorus (found in dairy products, cheese, dried beans, liver, nuts, and chocolate) and sodium, and monitoring the amount of fluids consumed.

Weight gain - Weight gain can be a problem for people undergoing peritoneal dialysis because the dialysate contains a high concentration of dextrose, a type of sugar. The body absorbs some of this dextrose during the dwell, which can lead to weight gain. A dietician can provide guidance on how to minimize weight gain by monitoring the number of calories eaten.

Body image - The abdomen will enlarge and may cause you to feel bloated when it is filled with fluid. You may need a larger size of clothing, and some people have a hard time accepting the change in their appearance. Patient support groups and websites can provide reassurance and tips for dressing.

Activities and peritoneal dialysis - In general, people using peritoneal dialysis should limit physical activities when their peritoneal cavity is full (has a large volume dwell). It is still possible to exercise and participate in sports, although you should discuss your activities with your physicians.

Time requirements - Peritoneal dialysis requires time and dedication, potentially interfering with other activities. This is especially true with CAPD, which requires the person to perform several exchanges during the daytime. Although it is possible to work and be active while using peritoneal dialysis, it may be necessary to cut back on responsibilities.

It is important to perform every exchange and dwell exactly as recommended. Skipping a treatment or performing a dwell for shorter or longer than recommended increases the risk of illness and the chances of being hospitalized, and can even shorten the person's life. If the demands of peritoneal dialysis feel overwhelming, or if you're having trouble performing all the necessary treatments, talk to a healthcare provider.

Dialysis and kidney transplantation are treatments for severe kidney failure, also called renal failure, stage 5 chronic kidney disease, and end-stage renal disease. There are two types of dialysis: hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. When the kidneys are no longer working effectively, waste products and fluid build up in the blood. Dialysis takes over a portion of the function of the failing kidneys to remove the fluid and waste. Kidney transplantation can completely take over the function of the failing kidneys. This article discusses these therapies, including the advantages, disadvantages, and care required for kidney transplantation and dialysis. You and your family should discuss all of the options with your healthcare provider to make an informed decision.

- Early in the course of kidney disease, medications are used to help preserve kidney function and delay the need for dialysis or transplantation. These early treatments are directed at the underlying kidney disease, secondary factors (such as hypertension) that promote kidney disease progression, and the complications of chronic kidney disease. As the kidneys lose their ability to function, fluid and waste products begin to build up in the blood. Dialysis should begin before kidney disease has advanced to the point where life-threatening complications occur. This usually takes many months or years after kidney disease is first discovered, although sometimes severe kidney failure is discovered for the first time in people who were not previously known to have kidney disease. It is best to begin dialysis treatments when you have advanced kidney disease, but while you still feel well. You and your doctor will decide when to begin dialysis after considering a number of factors, including your kidney function (as measured by blood and urine tests), overall health, and personal preferences.

Kidney transplantation is considered the treatment of choice for many people with severe chronic kidney disease because quality of life and survival are often better than in people who use dialysis. However, there is a shortage of organs available for donation. Many people who are candidates for kidney transplantation are put on a transplant waiting list and require dialysis until an organ is available. A kidney can come from a living relative, a living unrelated person, or from a person who has died (deceased or cadaver donor); only one kidney is required to survive. In general, organs from living donors function better and for longer periods of time than those from donors who are deceased. Some people with renal failure are not candidates for a kidney transplant. Older age and severe heart or vascular disease may mean that it is safer to remain on dialysis rather than undergo kidney transplantation. Other conditions that might prevent a person from being eligible for kidney transplantation include:

Active or recently treated cancer A chronic illness that could lead to death within a few years Poorly controlled mental illness (psychosis) Severe obesity Inability to remember medications Current drug or alcohol abuse

Most centres exclude people who are HIV-positive. In selected cases, however, people with HIV may be eligible for kidney transplantation if their disease is well-controlled. People with other medical conditions are evaluated on a case-by-case basis to determine if kidney transplantation is an option.

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for many people with end-stage renal disease. A successful kidney transplant can improve your quality of life and reduce your risk of dying from kidney disease. In addition, people who undergo kidney transplantation do not require hours of daily dialysis treatment.

Kidney transplantation is a major surgical procedure that has risks both during and after the surgery. The risks of the surgery include infection, bleeding, and damage to the surrounding organs. Even death can occur, although this is very rare. After kidney transplantation, you will be required to take medications and have frequent monitoring to minimize the chance of organ rejection; this must continue for your entire lifetime. The medications can have significant and bothersome side effects.

In haemodialysis, your blood is pumped through a dialysis machine to remove waste products and excess fluids. You are connected to the dialysis machine using a surgically created path called a vascular access, usually referred to as an access. This allows blood to be removed from the body, circulate through the dialysis machine, and then return to the body. Haemodialysis can be done at a dialysis centre or at home. When done in a centre, it is generally done three times a week and takes between three and five hours per session. Home dialysis is generally done three to seven times per week and takes between three and ten hours per session (often while sleeping). More detailed information about haemodialysis is available separately.

It is not known if haemodialysis has clear advantages over the other type of dialysis (peritoneal dialysis) in terms of survival. The choice between the two types of dialysis is generally based upon other factors, including your preferences, home supports, and underlying medical problems. You should begin with the type of dialysis that you and your doctors think is best, although it is possible to switch to another type as circumstances and preferences change.

Low blood pressure is the most common complication of haemodialysis and can be accompanied by light-headedness, shortness of breath, abdominal cramps, nausea, or vomiting. Treatments and preventive measures are available for these potential problems. In addition, the access can become infected or develop blood clots. Many patients who receive haemodialysis in a centre are either unable to work or choose not to work due to the time required for travel and treatment.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is typically done at home. To perform PD, the abdominal cavity is filled with dialysis fluid (called dialysate) through a catheter (a flexible tube). The catheter is surgically inserted into the abdomen near the umbilicus (belly button). The fluid is held within the abdomen for a prescribed period of time (called a dwell). The lining of the abdominal cavity (the peritoneal lining) acts as a membrane to allow excess fluids and waste products to diffuse from the bloodstream into the dialysate. The used dialysate in the abdomen is then drained out and discarded. The peritoneal cavity is then filled again with fresh dialysate. This process is called an exchange. The exchange may be done manually four to five times during the day. The exchange may also be done automatically using a machine (called a cycler) while you sleep.

Advantages of peritoneal dialysis compared to haemodialysis include more uninterrupted time for work, family, and social activities. Most people who use PD are able to continue working, at least part-time, especially if exchanges are done during sleep.

People who use PD must be able to understand how to set the equipment up and use their hands to connect and disconnect small tubes. If you cannot do this, a family or household member may be able to do it. Disadvantages of peritoneal dialysis include an increased risk of hernia (weakening of the abdominal muscles) from the pressure of the fluid inside the abdominal cavity. In addition, you can gain weight and you have an increased risk of infection at the catheter site or inside the abdomen (peritonitis).

- Kidney transplantation is the optimal treatment for most patients. Patients who are not candidates for kidney transplantation or who must wait for a kidney can usually be treated with either haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Choosing between peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis is a complex decision that is best made by you and your doctor, and often other family members or caregivers, after careful consideration of a number of important factors. For example, haemodialysis involves rapid changes of the fluid balance in the body and cannot be tolerated by some patients. Some patients are not suitable candidates for kidney transplantation, while others may not have the home supports or abilities needed to do peritoneal dialysis. Your overall medical condition, personal preferences, and home situation are among the many factors that should be considered. It is possible to switch from one type of dialysis to the other if preferences or conditions change over time.

Dialysis is available to everyone who needs it. However, some people choose to refuse dialysis. You and your family should discuss the risks and benefits of long-term dialysis early and often.

Most people with kidney disease who have no other chronic illnesses are encouraged to pursue aggressive treatment of their disease; the chance of having a high quality of life for an extended period of time is usually excellent. However, you may have compelling reasons for refusing treatment. Try to feel comfortable discussing your wishes with your family and healthcare team with the goals of death with dignity and life with quality.